In the picturesque fishing village of Cellardyke—once known as Nether Kilrenny—one might not expect to find echoes of political scandal and corruption. Yet in the late 18th century, this unassuming coastal town became a quiet microcosm of a much larger problem: the selling of democracy for personal gain. The scandal of 1767, now little more than a footnote in regional histories, was a revealing moment in the decline of an era when civic virtue gave way to the blunt influence of money.

At the time, Cellardyke was a burgh of regality—granted special privileges and representation through its ties to noble landowners. The town was grouped with several neighboring burghs including Pittenweem, Anstruther, and Crail for parliamentary purposes. In the complex system of Scottish local government, it was the town councils—made up of a small number of elected (or more accurately, self-elected) men—who decided which representative would go forward to Parliament.

And this is where things went wrong.

A Council of the "Indigent and Incorruptible"—Or Not?

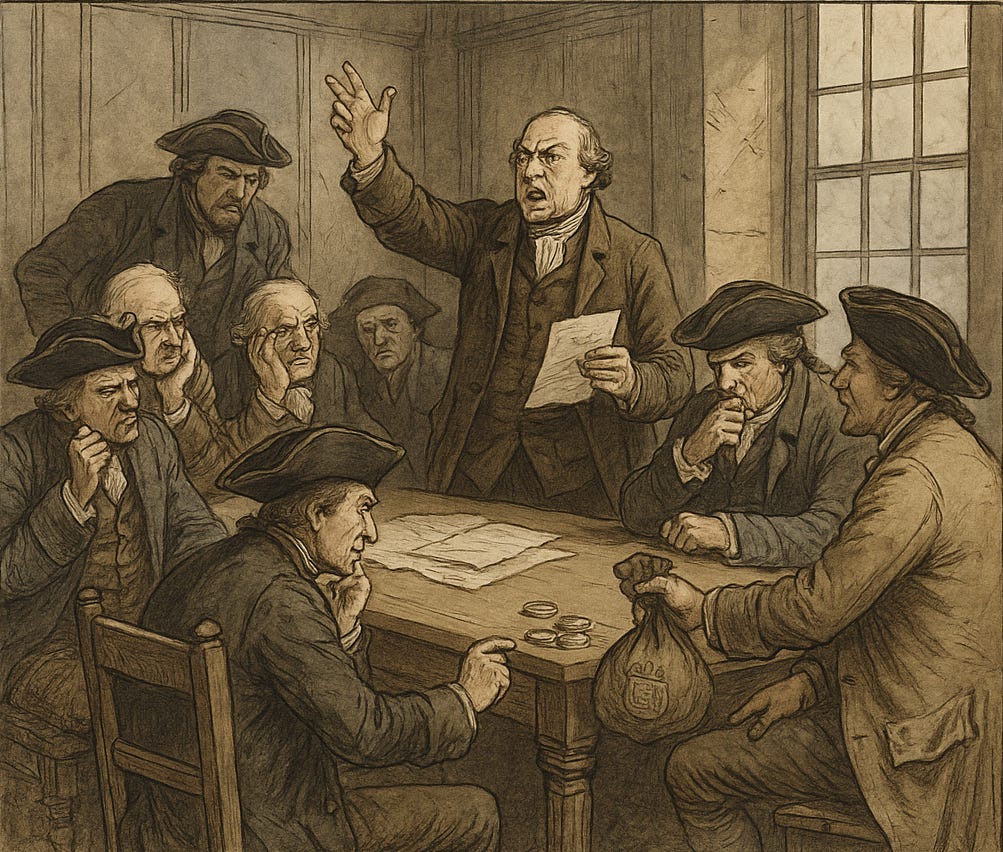

According to Morison’s Dictionary of Decisions, a legal reference compiled in the 19th century, by 1767 the town councils of Cellardyke, Pittenweem, and West Anstruther had developed a reputation for moral weakness and political pliability. Morison was particularly scathing about Cellardyke, describing its councillors as "low indigent persons incapable to resist any money temptation."

The method of council succession at the time made it easy for these patterns to persist. Under the system of the sett, the old council elected the new—essentially allowing existing members to select their successors. It was a self-sustaining oligarchy, cloaked in legitimacy but wide open to manipulation. Councils operated in small cliques and behind closed doors, wielding disproportionate influence over parliamentary elections. No ballots. No public debate. Just a few men with an opportunity—and often, a financial incentive.

In 1767, Cellardyke’s council was accused—credibly—of selling its vote in an upcoming parliamentary election to the highest bidder. The scandal wasn't just a local embarrassment. It was symptomatic of a much broader crisis in Scottish electoral politics, especially in smaller, poorer burghs where the line between necessity and corruption was razor thin.

Why Would a Fishing Town Sell Its Vote?

To understand the scandal, one has to consider Cellardyke’s economic condition at the time. Though once prosperous, the mid-18th century saw the town suffering from the decay of its once-mighty fishing industry. The once-glorious herring fleets had diminished. The haddock had mysteriously vanished from the coastal waters. Fishing boats grew fewer. Jobs disappeared. Poverty increased. It’s easy to understand how desperate townspeople—especially councilmen without means—might find themselves swayed by money.

A vote in Parliament, though only symbolic for some, had real consequences. Access to land grants, tax reliefs, or harbor improvements could all hang in the balance. Wealthy political aspirants, eager to gain a seat in Parliament, would bribe burgh councils with money, favors, or promises of patronage. In places like Cellardyke, this wasn’t just politics—it was survival.

Unfortunately, such survival often came at the cost of legitimacy.

In Cellardyke’s case, the 1767 scandal proved to be a breaking point. The revelation that the entire council was prepared to “sell themselves to the highest bidder” cast a long shadow. Though not prosecuted in court, the burgh’s reputation suffered. Its electoral independence became suspect. And with reform efforts on the horizon, its days of unchecked self-governance were numbered.

Disfranchisement and Reform: The Long-Term Fallout

By the 19th century, the consequences of repeated abuses of power in towns like Cellardyke became impossible to ignore. The Burgh Reform Act of 1833, part of a broader wave of political reform sweeping the UK, fundamentally changed the structure of local government. For Cellardyke, it meant the end of the old sett system and the beginning of municipal democracy based on voting rights, not patronage.

But even this came with pain. In 1828, five years before the Act, Cellardyke was disfranchised—stripped of its right to elect a member of Parliament. Instead, its affairs were handed over to appointed managers by the Court of Session. It was a humiliating but necessary step. A town that once held sway in regional politics was reduced to being governed by outsiders.

This administrative reboot did, however, open the door to recovery. Over time, the people of Cellardyke reclaimed civic pride, rebuilt their economy, and gradually restored local control. By the late 19th century, they had elected a provost, two bailies, and five councillors—no longer hand-picked but elected with accountability. These new leaders also served as Police Commissioners and oversaw local development projects, harbor management, and social services.

Today, Cellardyke stands as a model of small-town resilience. Its council scandal of 1767 serves as a cautionary tale—one that reveals how fragile democratic institutions can become under economic strain, and how communities must fight not just for prosperity, but for integrity.