The Cambuslang Religious Revival

The Cambuslang Religious Revival, or Cambuslang Wark, was a powerful and transformative religious movement that took place in Cambuslang, a small town on the banks of the River Clyde in Scotland, during 1742. This revival was a part of a larger evangelical movement sweeping through the country, ignited by the preachings of renowned ministers like George Whitefield and William McCulloch. It marked one of the most significant religious awakenings in Scottish history, and its impact was felt far beyond the boundaries of the small town where it occurred.

Background: The Evangelical Wave in Scotland

In the early 18th century, religious life in Scotland was undergoing significant changes. The Scottish Presbyterian Church, traditionally known for its stern Calvinism, had seen increasing calls for spiritual revitalization. The effects of the Great Awakening in the American colonies and England, with their emphasis on personal salvation and a direct, emotional relationship with God, were starting to be felt in Scotland. This broader context set the stage for the Cambuslang Revival, which would bring both religious fervor and intense controversy.

In the winter of 1741-1742, Mr. William McCulloch, the parish minister of Cambuslang, began to address his congregation in a more emotionally charged and spiritually demanding manner than had been typical in the past. Influenced by the evangelical style of preaching, McCulloch's sermons became increasingly focused on the themes of repentance, conversion, and the looming terror of hellfire for the unredeemed.

This shift resonated deeply with his parishioners, and soon, a religious excitement began to stir within the community. But it wasn’t until the arrival of George Whitefield in 1742 that the revival truly gained momentum. Whitefield, already famous for his evangelical revivals in England and America, brought a passionate energy to Cambuslang that would push the revival into overdrive.

The Revival at Cambuslang: Fervor and Convulsions

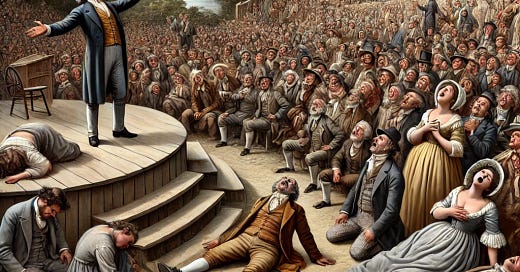

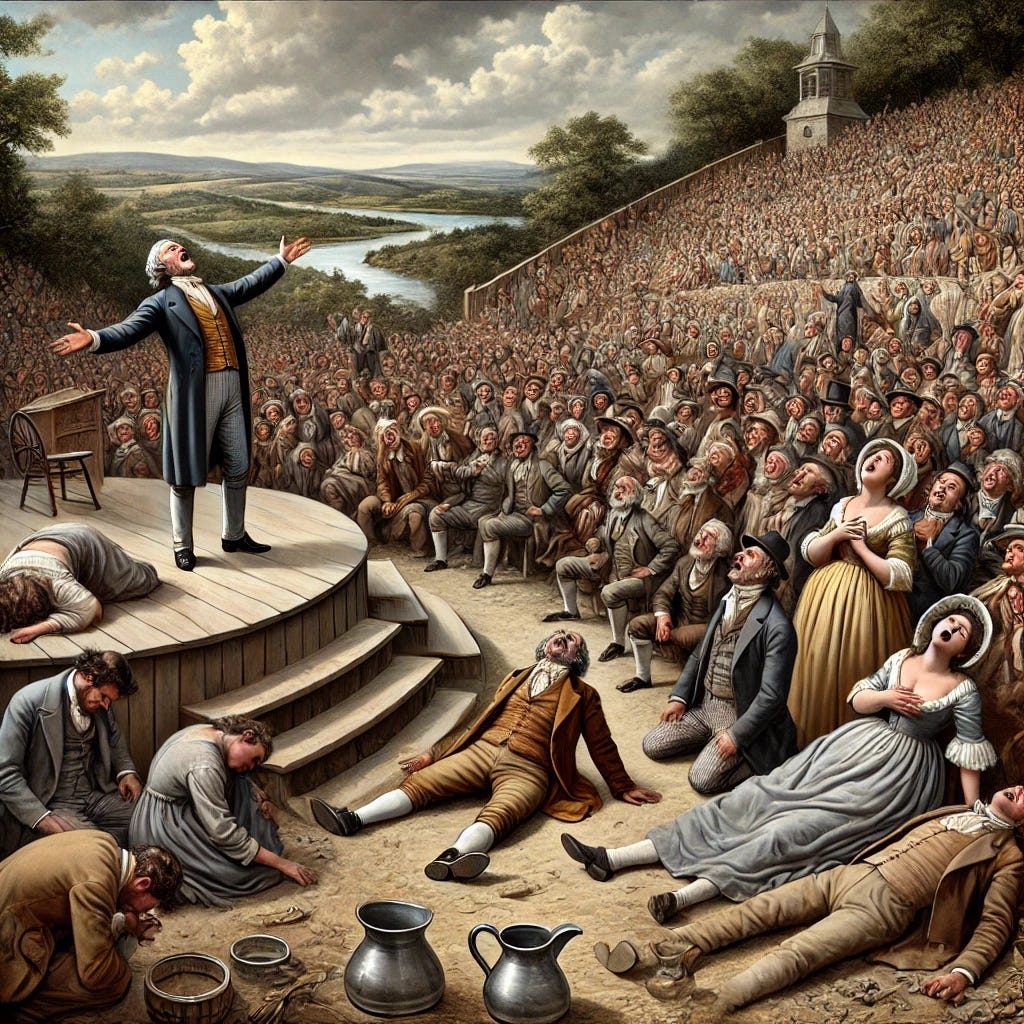

The Cambuslang Wark (the Scots term "Wark" meaning "work") erupted in the early months of 1742 and quickly became the focal point for evangelical activity in Scotland. What made this revival stand out were the highly emotional and physical manifestations of faith that began to appear during the services.

The primary location of the revival meetings was a natural amphitheater, or holm, on the banks of the River Clyde, where large crowds gathered to hear Whitefield and McCulloch preach. As the revival meetings continued, they drew participants not only from Cambuslang but from the surrounding regions as well. Many walked for miles to witness or experience this profound spiritual event.

During these gatherings, people were reportedly "seized" by the Holy Spirit, often in dramatic and physical ways. Accounts describe how individuals would fall to the ground in convulsive fits, crying out in fear of eternal damnation. Many fainted or swooned from the intensity of the sermons, while others wept openly in terror of their sins. Whitefield's preaching, which emphasized the doctrine of free grace and the need for personal regeneration, struck a deep chord with these people. For many, these public displays of emotion were seen as proof of genuine spiritual transformation.

Pitchers of water were kept nearby to revive those who had fainted, and a row of "patients" could often be seen seated at the front of the assembly, their heads bound with cloths as they recovered from their physical reactions to the intensity of the sermons. The spectacle was both awe-inspiring and frightening, drawing increasing attention from far and wide.

Controversy and Opposition

Not everyone, however, was convinced that what was happening in Cambuslang was a genuine move of God. The revival sparked a fierce controversy between different factions of the Scottish Church. The Seceders, a group of ministers who had broken away from the Church of Scotland in protest against what they saw as its increasing secularization and laxity, were among the loudest critics.

For the Seceders, the intense emotionalism and public displays of spiritual ecstasy were deeply troubling. They viewed the revival as a sign of God's anger with the established church, believing that the emotional outbursts and the perceived "miracles" were not of divine origin but were instead a "strong delusion" sent as a form of divine judgment. In response to the revival, the Seceders called for a national day of fasting and repentance, warning that Cambuslang was being overrun by false spirituality.

On the other hand, the clergy of the Established Church—particularly those sympathetic to evangelicalism—welcomed the Cambuslang Wark as a sign that the spiritual flame had not gone out in Scotland. They pointed to the many sinners who had repented and turned away from their evil ways, seeing this as evidence of a genuine work of the Holy Spirit. McCulloch and Whitefield, in particular, were convinced that the revival was a true outpouring of divine grace, arguing that the conversion of souls was the ultimate proof of its authenticity.

The dispute between the two sides became bitter and protracted, with each camp claiming to speak for God. Whether the Cambuslang Wark was a true religious awakening or a dangerous, misleading delusion depended largely on one's theological position.

The Legacy of the Cambuslang Revival

Despite the controversy, the Cambuslang Revival had a lasting impact on Scottish religious life. By the time the fervor died down later in 1742, it was estimated that 400 people in Cambuslang alone had undergone permanent spiritual transformation as a result of the revival. In addition, hundreds more in other parts of Scotland and beyond were believed to have experienced similar awakenings.

The Cambuslang Wark also left its mark on evangelical movements in Britain and the American colonies. George Whitefield continued to preach throughout the British Isles and America, spreading the message of the revival wherever he went. Cambuslang became a symbol of the power of evangelical zeal, and it influenced the course of the Great Awakening in the American colonies, which was similarly marked by emotional religious experiences and mass conversions.

For Scotland, the revival sparked a renewed interest in evangelical theology and religious participation. Many of the people who experienced the revival at Cambuslang became lifelong adherents of the evangelical faith, helping to spread its influence in their local communities.

At the same time, the revival’s more dramatic elements—the fainting, the weeping, and the convulsions—became a subject of fascination and controversy. Some viewed these physical manifestations as evidence of God’s direct intervention in the world, while others saw them as a dangerous form of fanaticism.

Conclusion

The Cambuslang Religious Revival was a complex and multifaceted event. It was a moment of intense spiritual fervor, marked by emotional outpourings, dramatic physical manifestations, and a sense of divine urgency. For those who experienced it firsthand, it was a life-changing event that brought them closer to God and transformed their understanding of faith.

However, it was also an event that exposed deep divisions within the Scottish Church, highlighting the tensions between the more traditional, doctrinal approach to religion and the rising tide of evangelical fervor. Ultimately, the Cambuslang Wark remains a key chapter in the history of Scottish religious life, a powerful reminder of the profound impact that religious belief can have on individuals and communities.