Throughout history, there have been countless stories of landlords and estate managers wielding unchecked power over their tenants. But few are as bizarre—and as cruel—as the practice of cutting off the ears of sheep to punish Highland crofters. This shocking act, carried out in the Isle of Skye in the 19th century, became known as the “Thief’s Mark.” It was not just an act of cruelty; it was a method of control, a symbol of oppression, and a chilling reminder of the desperate conditions in which many Highlanders lived.

This article explores the grim reality behind this punishment, the men who enforced it, and how it became one of the most infamous examples of landlord tyranny in Scotland’s history.

The Factor Who Marked Sheep—And People

In the early 1800s, much of the Isle of Skye was controlled by powerful landlords who owned vast estates. These landlords appointed factors—middlemen who collected rents, managed evictions, and ensured tenants obeyed estate rules. Factors were notorious for their heavy-handed methods, but one in particular stood out: Dr. MacLean of Talisker.

MacLean had a reputation for cruelty. Witnesses testified before the Royal Commission on Highland Crofters in the 1880s that he had a brutal way of dealing with crofters whose sheep wandered onto his land. Instead of simply fining the owners or returning the animals, he ordered that their ears be cut off as a permanent mark of shame.

To many, this was no different from branding criminals. The maimed sheep—easily identifiable by their missing ears—became a public warning that their owners had “stolen” grazing land from the estate. But in reality, these crofters were often just struggling to survive after being forced off their ancestral lands to make way for large-scale sheep farming.

The Highland Clearances and the Battle for Land

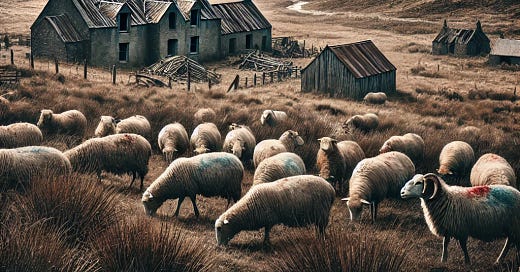

To understand why such punishments occurred, we must look at the Highland Clearances, one of the darkest chapters in Scottish history. During the 18th and 19th centuries, landlords across the Highlands evicted thousands of small farmers—known as crofters—to make way for profitable sheep farms. Entire communities were uprooted, their homes burned, and their lands seized. Many were forced into overcrowded coastal villages or left Scotland altogether, emigrating to Canada, Australia, or the United States.

For those who remained, life was desperate. Land that had once supported entire villages was now in the hands of a few wealthy sheep farmers. Crofters who had previously grazed cattle and sheep freely were now banned from using pastures their families had farmed for generations. If a crofter’s sheep strayed onto a landlord’s land—sometimes by accident, sometimes out of sheer necessity—it could result in a harsh penalty.

This is where MacLean’s “Thief’s Mark” came into play. It was designed not just as a punishment but as a form of psychological warfare. A crofter whose sheep had been marked was publicly shamed and, in many cases, financially ruined.

Fear, Resistance, and the End of the Practice

Despite the fear that factors like MacLean spread, the crofters were not passive victims. Throughout the Isle of Skye, resistance grew. Protests, legal challenges, and acts of defiance became more common. In places like Glendale and the Braes, crofters banded together to challenge the landlords and their factors.

One of the most significant turning points came when the Royal Commission on Highland Crofters was established in the 1880s to investigate these injustices. The testimonies given before the commission exposed the brutal methods used against crofters, including forced labor, unjust evictions, and the infamous “Thief’s Mark.”

When Dr. MacLean was confronted about the practice, he did not deny it. Instead, he claimed it had been a common method of discipline before his time—an admission that only fueled public outrage. The revelation that such cruelty had been systematically carried out in Skye for years became a turning point in the fight for crofters' rights.

Following the commission’s inquiry, changes were gradually introduced to Highland land laws. The Crofters' Holdings (Scotland) Act of 1886 granted crofters greater security, preventing them from being arbitrarily evicted and allowing them to maintain permanent tenure of their land. Though far from perfect, this law marked the beginning of the end for landlord tyranny in the Highlands.

A Lasting Symbol of Oppression

Today, the story of Skye’s “Thief’s Mark” serves as a disturbing reminder of how power can be abused when laws favor the wealthy over ordinary people. It also highlights the resilience of the Highland crofters, who—despite oppression, hardship, and exile—continued to fight for their land and their way of life.

The physical scars left on the sheep of Skye may have faded, but the memory of that cruel punishment remains. It stands as a symbol of a time when landlords ruled unchecked, when crofters were treated as little more than trespassers on their own land, and when survival often depended on resisting those in power.

Today, visitors to Skye can walk through the empty glens and abandoned villages left behind by the Clearances. Though the land is peaceful now, the echoes of the past remain—a reminder of a struggle that, in many ways, still resonates in Scotland’s ongoing debates about land ownership and rural justice.