It was an ordinary day in Stirling when the alarm was sounded—the French were coming.

In the backdrop of the Napoleonic Wars, with tension constantly simmering and rumors of invasion swirling like Scottish mist, a single word could send a village into full-blown panic. And that word, shouted by a galloping farmer careening into town, was “French!” Behind him trailed whispers, hurried footsteps, and rising fear. Were the dreaded soldiers of Bonaparte really advancing?

Not quite.

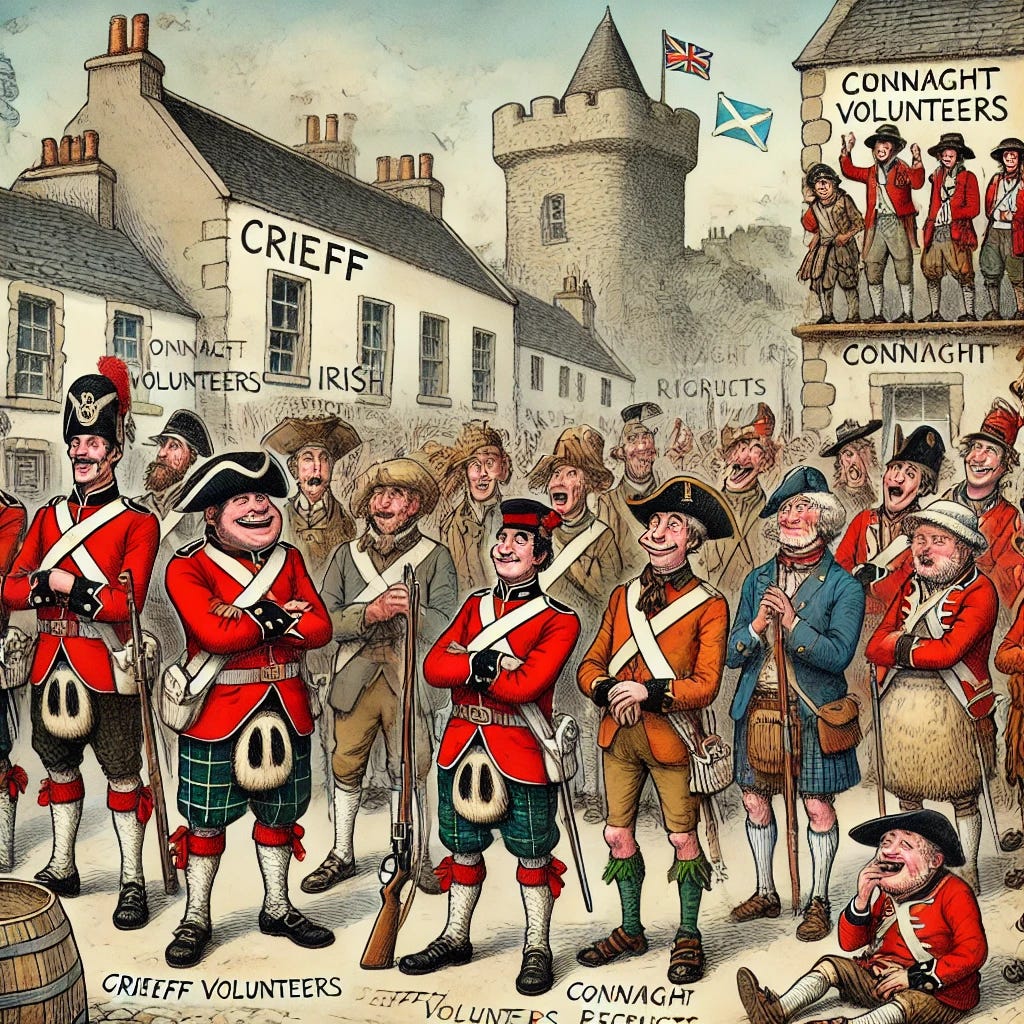

As it turned out, the enemy wasn’t French—but Irish. And not even enemy Irish. These were Connaught recruits, an oddball, ragtag group of men who had just been pressed into service. Yet, their appearance was so startling, so otherworldly to the locals, that they could have been space invaders for all the terror they caused.

When the Tattie-Bogles Came Marching In

The Crieff Volunteers, a disciplined (albeit eccentric) local force, had marched proudly into Stirling and taken up residence in Stirling Castle. All was well until word arrived that a new unit was arriving to relieve them: a freshly raised Irish corps from Connaught—untrained, un-uniformed, and, to put it mildly, utterly unkempt.

These men didn’t look like soldiers. They looked like tattie-bogles—Scottish scarecrows. Some had red military coats patched with blue civilian fabric. Others had trousers stitched together with rope. Many were shoeless, yet every single one wore a hat—even if it looked like it had been salvaged from a pirate shipwreck.

This phantasmagoric force made its way into Stirling like a disheveled tide, prompting widespread hysteria. Locals locked their doors, whispered of Papist invasions, and thanked God that the Crieff lads were armed.

The Crieff men, for their part, had seen French POWs before in Perth and knew right away these weren’t Frenchmen, but their sense of humor was tickled more than their sense of danger.

Panic in the Parish: Stirling Revolts

As the Connaught contingent spread into the town with their billets in hand—ready to be hosted in local homes—the reaction was swift and fierce. Householders slammed doors, gossiped furiously, and began a petition.

The plea to the magistrates? If soldiers must be billeted, give us the Crieff men instead—lock the Irish ones in the castle!

It worked. The Stirling authorities reversed course, reassigning the Crieff men from the fortress to the town. The Irish were relocated behind castle walls, becoming Stirling’s most unwanted houseguests—garrisoned not for defense, but for containment.

A Parade to Remember—for All the Wrong Reasons

The next day, curious townspeople gathered to inspect these peculiar newcomers during their parade. What they saw confirmed all their worst fears—and then some.

There wasn’t a complete military outfit among the lot. Uniforms looked like Frankenstein’s tailoring, stitched together from whatever materials could be found. One soldier wore a half-red, half-grey coat with blue skirt extensions. His arms bore two stripes of uncertain origin, and he secured his trousers with straw rope garters.

Some wore partial shakos; others wore “pirn hats”—hollowed-out bobbin-caps more fit for spinning thread than combat.

Despite all this, one soldier stood out—their dandy, if such a word could be applied. The Crieff lads named him their “Beau Brummel”. Dressed in a complete (albeit mismatched) uniform and proudly marching, he was a walking contradiction—half parade, half parody.

The Crieff Volunteers: From Laughed At to Lifesavers

The Crieff regiment, long viewed by some with mild amusement for their quirky “Daft Company” and rustic antics, suddenly found themselves in high favor. Households once annoyed by pack-thread covered uniforms and unbrushed red coats now gladly welcomed the lads.

They may have been rough, but they weren’t terrifying.

Where the Connaught men had been met with suspicion and dread, the Crieff lads were now embraced as respectable defenders of the realm, albeit slightly eccentric ones.

One resident put it best when, in reference to the Irish, they cried out:

“Heaven save us from our friends!”

When the French Were Irish and Order Was Restored

In the end, the Connaught men didn’t cause any violence—they simply existed too loudly, too bizarrely, for the refined sensibilities of Stirling’s citizens. But their arrival highlighted something vital: even in wartime, appearances mattered.

It also showcased the deep fear and cultural mistrust that existed between Scotland and Ireland at the time. The French may have been the enemy, but the unknown and the “other” felt far more threatening to daily life than distant Napoleon.

The Crieff Volunteers returned home shortly after, remembered less for their discipline and more for their reliability. Stirling breathed easier, the castle held firm, and the townspeople learned that not every wild-looking soldier is a foe—but not every friend is welcome either.