In the 18th century, Scottish ministers were expected to be paragons of virtue, guiding their congregations with wisdom, sobriety, and a deep reverence for the divine. But John Carlyle of Inveresk—despite his clerical robes—was not exactly a traditional man of the cloth. Instead of spending his evenings in quiet prayer and theological study, he was more likely to be found dining at aristocratic tables, playing cards with the elite, and, as some alleged, belting out questionable songs after a few too many drams of whisky.

One such song, De’il Stick the Minister, landed him in hot water. The title alone—roughly translating to "May the Devil Stab the Minister"—was enough to make pious churchgoers clutch their Bibles in horror. But when word spread that a minister himself had been caught singing it at a gathering, the scandal ignited.

Carlyle: The Clergyman Who Lived Like a Lord

Carlyle was no ordinary minister. He was strikingly handsome, socially ambitious, and deeply involved in the world of the Scottish Enlightenment. His congregation at Inveresk, just outside Edinburgh, was made up of wealthy patrons who enjoyed the finer things in life—fine dinners, theatre, and a liberal approach to religion.

Unlike his Evangelical rivals, who preached fire-and-brimstone sermons and denounced worldly pleasures, Carlyle embraced the genteel lifestyle of the upper classes. He played golf, danced at society balls, and famously defended the right of clergymen to attend the theatre. He even helped introduce card games into respectable homes, arguing that a little entertainment did no harm.

But there was a fine line between being a cultured gentleman and a scandalous clergyman, and Carlyle was about to cross it.

A Drunken Night and a Damning Accusation

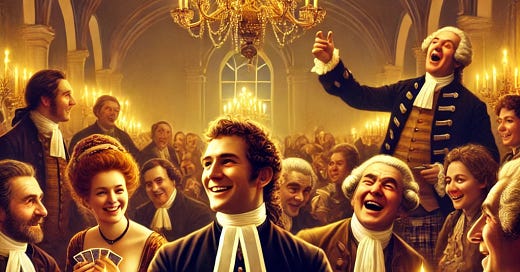

At a lively social gathering—possibly in a country house after church service—Carlyle was reportedly in high spirits. Drinks flowed, conversation sparkled, and someone (perhaps emboldened by whisky) struck up a song. The tune? De’il Stick the Minister.

The lyrics, full of irreverent humor, mocked the very profession Carlyle represented. They painted ministers as pompous, hypocritical, and out of touch—an image that Evangelicals had long accused the Moderates of embodying. Some versions even suggested that ministers deserved a good beating or worse, courtesy of the devil himself.

Did Carlyle actually sing it? His opponents certainly thought so. The story spread like wildfire, and soon pamphlets were circulating that painted him as a blasphemous rogue who spent more time entertaining ladies and playing cards than tending to his flock.

His Evangelical critics, already suspicious of the Moderate clergy’s lax moral standards, seized on the opportunity. Here was proof, they claimed, that the Church of Scotland was in decay. Ministers were no longer shepherds of the faithful—they were socialites, entertainers, and, in Carlyle’s case, revelers who openly mocked their own calling.

Defending the Indefensible?

Carlyle, of course, did not take the accusations lying down. He was a sharp-witted man with powerful allies, and he had no patience for religious zealots who clung to old-fashioned piety. He dismissed the scandal as yet another attempt by Evangelicals to smear the Moderates, whom he saw as the true intellectual leaders of the Church.

He argued that the Church should not be a place of rigid puritanism, but of rational thought and social engagement. If ministers were educated men who could move in high society, why should they be condemned for enjoying themselves? As for De’il Stick the Minister, he likely laughed it off, treating it as harmless fun rather than an attack on faith.

Nevertheless, the scandal tarnished his reputation among conservative churchgoers. Though he retained his post and remained a leading figure in the Scottish Enlightenment, the incident added to his growing notoriety as the minister who seemed to have everything—except the appearance of holiness.

The Legacy of a Scandalous Song

Looking back, Carlyle’s alleged performance of De’il Stick the Minister is more than just an amusing anecdote. It highlights a critical moment in Scottish religious history when the Church was caught between two forces: the intellectualism and social refinement of the Moderates, and the strict moralism of the Evangelicals.

To his admirers, Carlyle was a modern, enlightened man who refused to be shackled by outdated religious expectations. To his detractors, he was living proof that the Church was losing its way.

Whatever the truth of that fateful evening, one thing is certain: few ministers have ever been accused of drunkenly cursing their own profession in song. And even fewer have emerged from such a scandal with their reputations—mostly—intact.