Why Scots Refused to Eat Fish Despite Its Abundance

Scotland, with its rugged coastline, abundant lochs, and fast-flowing rivers, has always been a land of plenty when it comes to fish. From salmon and trout to herring and cod, the waters of Scotland teem with life, providing a natural bounty for its people. Yet, historically, the Scots were known to consume remarkably little fish, especially compared to other seafaring nations. This intriguing paradox is rooted in a complex web of cultural, religious, and social factors that spanned centuries, primarily from the medieval period to the early modern era.

A Matter of Culture and Perception

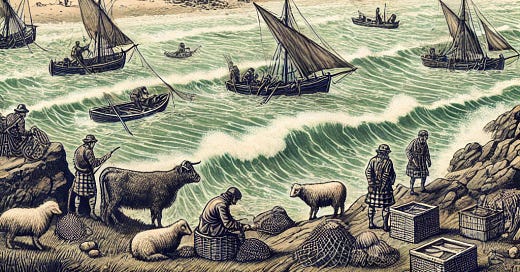

From the 12th to 16th centuries, the Scots' relationship with fish was shaped by cultural attitudes that associated it with poverty and necessity. Fish was often viewed as the food of the destitute, while meat symbolized wealth and status. For the affluent classes, whose social standing was tied to land ownership and livestock, meat from cattle, sheep, and game was central to their diet. Fish, on the other hand, was regarded as a fallback food for those without access to these resources.

Scotland’s predominantly pastoral economy during the Middle Ages reinforced these dietary preferences. Sheep and cattle thrived in the hilly terrain, and dairy products, beef, and mutton became staples of the Scottish diet. The rugged landscape made animal husbandry a practical choice for much of the population, while fishing, though feasible in coastal areas, was less integrated into the daily lives of inland communities.

Religious Influences: A Fishy Divide

Religion was another powerful force influencing dietary habits in Scotland, particularly between the 14th and 17th centuries. During the medieval Catholic era, fish played a significant role in the diet due to religious fasting practices. Lent and other holy days required abstinence from meat, making fish a vital alternative. However, the Scottish Reformation of the 16th century brought a seismic shift in religious practices, as Presbyterianism replaced Catholicism as the dominant faith.

Protestant reformers rejected many Catholic traditions, including dietary restrictions associated with religious observance. Practices such as eating fish on Fridays or during Lent faded from daily life, diminishing the role of fish in the Scottish diet. In the Protestant worldview, fish became a cultural relic of the old Catholic order, further reducing its appeal. By the 17th century, fish consumption had declined significantly among the general population.

The Practical Challenges of Fishing

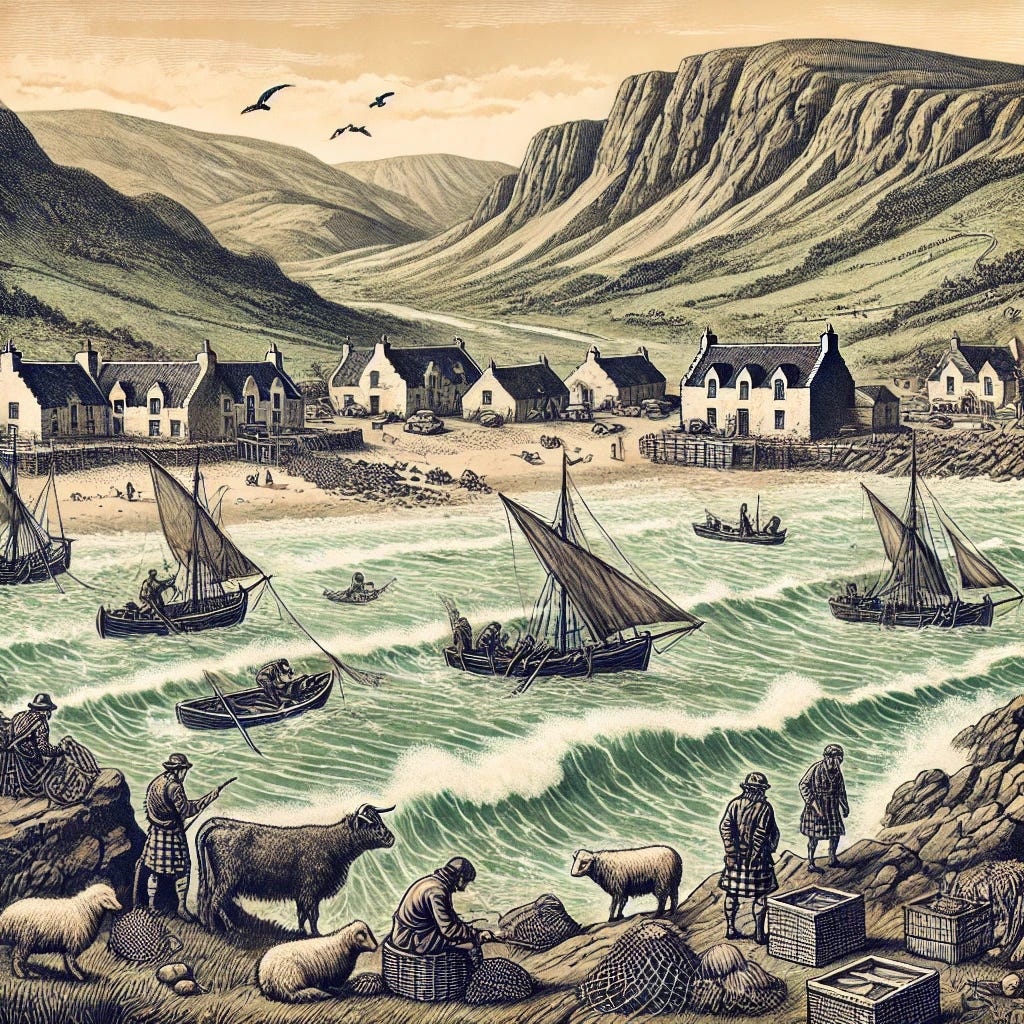

Despite Scotland's rich aquatic resources, practical challenges also played a role in the limited consumption of fish from the medieval period through the 18th century. Fishing was labor-intensive and required significant skill and effort. Coastal communities fished for their sustenance, but inland populations faced greater difficulties in accessing fresh fish. Before the advent of refrigeration or modern preservation techniques, fish spoiled quickly, making it impractical for many households.

Preserved fish such as salted herring or dried cod (stockfish) was available, but these were often imported from places like Norway and the Netherlands. Imported fish was expensive, and reliance on such goods conflicted with the Scots' cultural emphasis on self-sufficiency. Additionally, salmon and trout from rivers and lochs were often monopolized by the aristocracy or the church, leaving common people with limited access. This trend persisted into the 19th century, when fishing rights remained closely guarded.

The Sea as a Source of Ambivalence

Between the 15th and 18th centuries, Scotland’s ambivalent relationship with the sea further influenced dietary habits. While coastal communities relied on the ocean for sustenance, the sea also represented danger and uncertainty. Violent storms, shipwrecks, and piracy were common, fostering a wariness of the ocean. Inland communities, distanced from the coasts, lacked a cultural connection to the sea, reinforcing their preference for land-based resources like meat and dairy.

A Culinary Shift in the 19th and 20th Centuries

It was not until the 19th century, during the Industrial Revolution, that attitudes toward fish began to shift. Improvements in fishing techniques, transportation, and preservation methods made fish more accessible to the broader population. The rise of urban centers and the demand for affordable food led to an increase in fish consumption, particularly in the form of dishes like fish and chips, which became a staple of working-class diets by the late 19th century.

This period marked the beginning of a transformation in Scottish cuisine, as fish reentered the national diet on a larger scale. By the 20th century, fish had shed much of its historical stigma and became a valued component of Scottish culinary tradition.

Conclusion

The historical reluctance of Scots to eat fish despite its abundance was shaped by a combination of cultural, religious, and practical factors spanning the 12th to 18th centuries. While fish was once associated with poverty and Catholic traditions, these perceptions began to change in the 19th century with the advent of modern fishing and preservation techniques. Today, Scotland’s rich aquatic resources are celebrated in its cuisine, showcasing a remarkable evolution in dietary habits over the centuries.