Edinburgh Castle in the late 1470s was more than Scotland’s vault of state; it was a political pressure cooker. James III, beset by nobles who distrusted his favourites, had clapped his own brother—Alexander Stewart, Duke of Albany—into the fortress looming over the city. Albany, a swaggering jouster and sometime Lord High Admiral, knew that incarceration on “the rock” rarely ended with a mild pardon; royal brothers had an alarming habit of meeting sharp objects or quiet poisons. He needed a door out, and there was none.

Enter a stroke of sideways thinking that still reads like a heist film: smuggling the tools of escape into the prison rather than smuggling the prisoner out. The accomplices? A French merchant captain anchored off Leith pier, a handful of low-profile sympathisers inside the court, and several small casks of Gascon wine—items no garrison officer would refuse.

The Rope in the Runlet

Medieval supply chains ran on trust and thirst. Foreign wine was a prestige commodity, and Edinburgh’s warders prided themselves on welcoming “gifts” for illustrious detainees. Into two of those knee-high wooden runlets—each holding twenty or so litres—conspirators coiled a knotted hemp rope, a wax-sealed message and a narrow dagger. They topped the barrels with real claret, wedged the bungholes, and sent them uphill from Leith with the routine victual convoy.

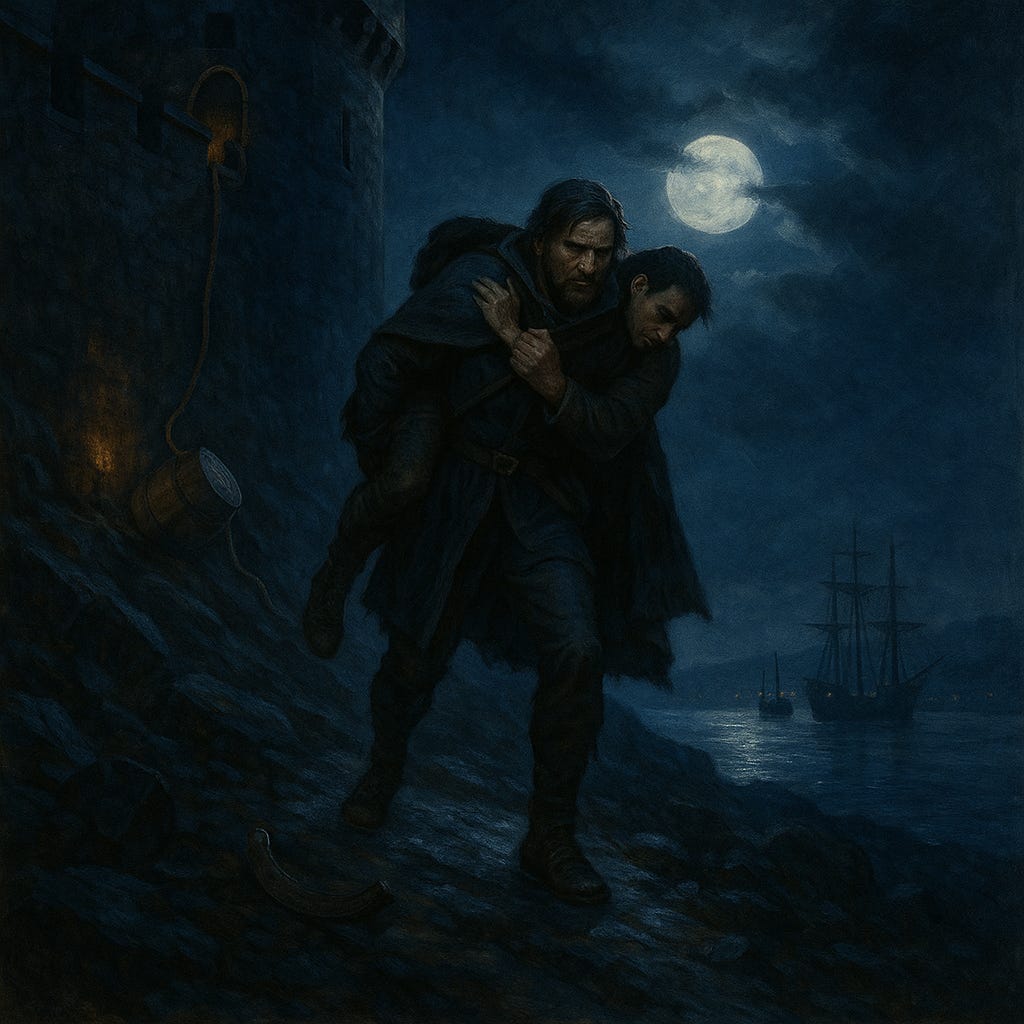

When the guards rolled the casks into Albany’s chamber, he uncorked more than wine. The note warned that the king’s council planned to arraign—and probably execute—him at next sunset. He had one night to act. After the warders had sampled enough of the “gift” to slump into a stupor, Albany used the dagger and his own remarkable strength to dispatch or disable them. Then came the rope. At a window carved into the vertical basalt face above Princes Street, he braced, prayed, and began to lower himself into darkness. His sole attendant, a groom named Thomas Dixon, slipped and broke his leg on the way down; Albany hoisted the injured man onto his shoulders and finished the descent burdened but unbroken.

Descent into Legend

Below the castle rock, a skiff from the French wine-ship bobbed against the Nor’ Loch’s marshy fringe. The fugitives limped aboard and followed the Water of Leith to the harbour, where the captain weighed anchor at dawn. By the time garrison sergeants saw a rope swinging in the morning mist—the classic tell-tale of an escape—Albany’s sail was a shrinking fleck in the Firth of Forth.

Contemporaries were stunned less by the boldness than by the theatrics:

Weaponised hospitality – Wine barrels were the garrison’s weakness; the duke turned it into a Trojan Horse.

Vertical exit strategy – No tunnelling, no bribed gatekeepers; just gravity, grit, and good ropework.

Loyalty repaid – Carrying an injured servant rather than abandoning him burnished Albany’s knightly image, feeding folk-songs from Edinburgh to Dunbar.

Fallout on Crown and Capital

James III awoke to scandal. A castle breach humiliated his regime, encouraging already-restless barons to question royal competence. Albany, meanwhile, courted France and England, styling himself “Alexander, King of Scotland” in continental proclamations. Though his later invasions fizzled and he died in a tournament accident in 1485, the jailbreak damaged his brother’s credibility so badly that James III never fully recovered—culminating in the king’s death at Sauchieburn (1488).

For Edinburgh and Leith the episode underscored twin truths:

Edinburgh Castle could be cracked. Subsequent captives were watched with harsher eyes, and new iron gratings appeared on windows that still scar the masonry today.

Leith was the indispensable bolt-hole. The port’s wharves hosted departing princesses, arriving artillery—and, when intrigue flared, the getaway craft of desperate nobles. Commerce boomed on that reputation for swift passage; every escape tale added a layer of myth to the harbour’s cobbles.

Albany’s rope-in-a-runlet remains a masterclass in medieval improvisation—proof that even impregnable walls can be undone by a well-placed cask and a splash of human audacity.